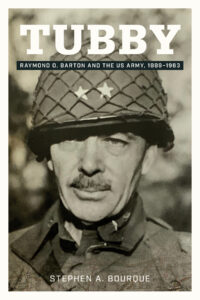

Editor’s note: In commemoration of the 80th anniversary of the D-Day allied invasion on June 6, we present an excerpt from the forthcoming biography of Army Maj. Gen. Raymond O. “Tubby” Barton by Stephen A. Bourque, professor emeritus at U.S. Army Command and General Staff College. It will be published in November by the University of North Texas Press.

At West Point, Barton’s abilities on the football field and wrestling team earned him the nickname “Tubby,” used by his friends and fellow officers for the rest of his life. He served as commander of the 4th Infantry Division, which landed on Utah Beach on D-Day, and he led the division through 204 days of continuous combat as it fought through German defenses on its way into Cherbourg. He became the first American general to cross the border into Nazi Germany.

The excerpt is from Chapter 9: Utah Beach, June 1-9.

***

Like almost all commanders, there was little Barton could do that night or morning. His unit was well trained, and he had his experienced leaders, [Brigadier General Ted] Roosevelt and [Colonel James] Van Fleet, landing in the initial assault. Barton got little sleep that night and spent most of it in the operations room aboard the USS Bayfield, looking at maps and charts. Onboard was the VII Corps staff, but none of the other principals, such as [Major General Joseph Lawton] Collins or his Chief of Staff, [Colonel Richard G.] McKee, mentioned any discussions or meetings that night. Finally, at about 04:30, the soldiers began loading into their landing boats.

Barton walked around the ship and gave the troops a motivational speech when he could. Then he watched as his troops left the Bayfield, dropped into their Higgins boats waiting below, and headed for the coast. As dawn broke, Barton observed the Ninth Air Force’s bombardment of the beach targets. At 05:50, the battleships Nevada, Enterprise, five cruisers, and eight destroyers began a bombardment of the Utah Beach defenses.

The reporter Ira Wolfert was standing next to the division commander as he watched the action. He asked: “How do you think it will go general?” Barton replied, “It has to go—there’s no place for those lads of mine to come back to.”

Company F, E, C, and B, 8th Infantry, hit the beach at precisely 06:30 hours. Roosevelt went in with Company B and began coordinating the two 8th Infantry assault battalions; Lieutenant Colonel Conrad C. Simmons 1st and Carlton O. MacNeely’s 2nd Battalion. Barton then observed the 22nd and 12th Infantry regiments forming up and heading to shore. Red Reeder later remembered the radio call before climbing into his landing craft: “Cactus to Cargo, come in.” Reeder responded to Barton: “Come in Cactus.” Then: “Good luck, Red.”

Within a few minutes on the beach, the two battalion commanders began telling the brigadier that the actual beach terrain bore little resemblance to the sand tables and maps they had been pouring over for months. While the battalion leaders were busy trying to get their troops productively engaged in battle and moving forward, Roosevelt had time to survey the beach area. The veteran of previous assaults realized they were in the wrong place. He got his bearings, located where they should be, and moved from one commander to the other, orienting them on their actual locations. He instructed MacNeelys and Simmons to clear the strong points in front of German troops and head toward their original objectives.

At 07:20 hours, Van Fleet arrived on the beach with the 3rd Battalion, and Roosevelt updated him on the situation and his decisions. The regimental commander concurred; he was the one in command, not the brigadier, and reported the decision back to Barton on the USS Bayfield. The follow-on units received instructions to follow the 8th onto the modified landing site. Both Van Fleet and MacNeely emphasized in their reports that Roosevelt was under machine gun and artillery fire during the entire period he was moving across the beach. They were impressed with his poise under fire and his leadership effectiveness. As the veteran in the group, he was the one that decided on the preferred course of action. Unfortunately, Simmons died in action on June 24, so we have no report from him on what he observed during the landing.

As a lieutenant with the 22nd Infantry, Bob Walk served as a liaison officer between his regiment and division headquarters. He was on the LCT that served as the vessel for the liaison and radio jeeps and other vehicles from the headquarters command group. This cramped boat also served as Barton’s command post as the fight began.

Bouncing alongside the Bayfield, Barton used the hood of Walk’s Jeep as the table for his situation map. There he listened to the reports from shore and monitored the action. Walk remembered Van Fleet’s reporting that everything was under control. It would have been about now when the commander received word of the adjustment to the landing beach. He checked his map, approved Van Fleet and Roosevelt’s adjustment, and passed the information on to Moon and Collins. Then Walk heard [Colonel Herve] Tribolet, his regimental commander, calling in and reporting that everything was going according to plan. After that report, he heard Barton say: “That’s enough for me, let’s go.”

First CPs Utah Beach June 6, 1944

Although Barton would spend almost 188 days in combat, it was the first one that, in many ways, was the most important. By now, he had nearly two full years of training and leading the division. But, he had more than that, including his time as chief of staff and 8th Infantry commander. He had supervised its preparation for combat in extensive exercises and amphibious training in Florida and England and knew all of the division’s senior officers and most of the company commanders personally.

Few American units would be as prepared for their first day of battle as the Ivy Division. Yet, this was his first taste of actual combat after thirty-six years in uniform. Barton told Cornelius Ryan, who interviewed him ten years after D-Day that he constantly fretted that he would become so afraid that he would freeze and fail as a combat leader. On June 6, he would discover which was more robust: his natural human fear or character developed in decades of preparing for this day.

As expected, the division’s official log of events, and subsequent after-action report for June 6, do not have the details historians would like. The staff officers were on the move and struggling to establish the first command post on the continent. But, thanks to Barton’s communications with [Cornelius] Ryan and the detailed comments from [Captain] Bill York’s diary, we now have an accurate account of the division commander’s actions on June 6.

[Brigadier General] Henry Barber and the division’s advance party had landed around 09:00 and moved beyond the beach as the 8th Infantry cleared the way to the causeways. Around 10:00, Barton, [Jason] Richards, and York arrived on the shore. Barton later admitted he was terrified as the sounds of the machine gun, rifle, and artillery fire surrounded him. A German artillery shell exploding nearby only increased his concern. He encountered the engineers behind the seawall, noted at the beginning of this chapter, and continued moving inland. He did not go far, but around 10:30 found a house with a high brick-walled courtyard on the dunes. The German artillery was increasing its fire rate, and anything on the beach was a potential casualty, so the house gave some protection.

Barton is quite open that there was little he could do at this point, his regimental commanders had a plan, and Roosevelt was on the ground making the needed adjustments. While at the beach house, Barton had little idea what was going on. “I was in a semi fog. No contact nor communications with anyone but those present… About a mile off our planned landing point. No idea of where nor how my assault battalions were, except that I did know they had taken their beach and gone on inland.” The only influence he had on the battle was when commanders of the attached units found him and asked if he had any instructions. In every case, he said: “No; just go ahead on your job per plan.”

Barton was sending his liaison officers and others to find out the situation. Lieutenant Joseph Owen remembered that at about 11:00, Barton sent him toward Sainte-Mère-Église to find the exact location of the 8th Infantry. On his way, he remembers running into Roosevelt, who slowed down his Jeep to yell out, “Hey Boy, they’re shooting up there, ” followed by a big “Haw Haw.” One constant among 4th Infantry Division soldiers that morning was the ubiquitous Roosevelt. Without fixed command responsibilities, he could range across the beach area, advising, conjoining, and keeping things moving. Owen found Van Fleet, and the colonel instructed one of his officers to mark the battle map for delivery back to Barton.

By noon, his battle staff, those who landed to assist during the early hours of the invasion, began to join him. One of the first was Colonel Dee Stone, the G-5 (Military Government), who had found Major Phil Hart, his former aide and now one of his staff officers, severely wounded at the water’s edge. The amphibious engineers present (under the sea wall’s shelter) refused to help Stone rescue Hart from the advancing tide, but he was able to move the wounded officer to safety. Then Dick Marr, the G-4, and Parks Huntt, his headquarters commandant, arrived, reported, and began moving toward the planned headquarters site.

Next reporting in was Colonel James E. Wharton, the 1st Engineer Special Brigade commander and the senior commander for the soldiers Barton encountered at the sea wall. As he notes in his letter to Cornelius Ryan ten years later: “The colonel took the trouble to inform me that his men were not the only ones quitting their missions at the seawall but that some of mine had done the same—in the beginning that was true but Ted Roosevelt cured that.” One suspects the division commander let him know how he felt.

Around 13:00, Barber’s aide found the division commander and guided him to a temporary command post, an impromptu collection of vehicles and staff officers just south of Causeway 2. Orlando Troxel (G-3) and Harry Hansen (G-2) and their small staff were monitoring the combat teams’ progress. Dick Marr reported that the infantry had crossed the low ground the Germans had flooded and were making good progress inland. All reports indicated that everything was generally going according to plan. There was little Barton could do; he had to let the commanders do their jobs.

However, he noticed that many follow-on units were backing up on the causeways and having trouble moving inland. He saw that the causeway was loaded with vehicles bumper to bumper but not moving. Without intending to, soldiers performing their assigned local duties made it difficult to get the division’s combat power into the fight. Engineers improving the route, antiaircraft guns, and wire teams were all making movement difficult. Finally, Barton and Marr went to the traffic jam, took a look, and ordered everything non-essential off the road. Some vehicles had broken down, and Barton had soldiers move stuck vehicles off the road and into the swamp. Once traffic across the causeway was flowing, troops would spend the rest of the night pulling the unfortunate equipment that got in the way out of the mire.

Troxel received reports that the division had captured Causeway #3 (T7), just to the north, and it was open for use. Nearby, Lieutenant Colonel Clarence G. Hupfer’s 746th Tank Battalion was still near the landing area, and Barton wanted it off the beach and to its next position near Audouville-la-Hubert.

Because of the congestion in front of him, he began developing an alternate route for the armor, using the reportedly open road. In the middle of all that confusion, around 15:00 hours, Roosevelt arrived at the temporary command post.

They joyfully embraced each other. Of course, Ted wanted to talk. Barton later noted: “He was bursting with information (which I sorely needed). —but wouldn’t let him talk.” He was under pressure to get the tank battalion into the fight. He later noted: “Try some day to keep a Ted Roosevelt from sounding off if he wants to—but I did.”